The Trip Explained

Through sheer coincidence and a bit of luck, I joined a crew on a sailboat participating in the 2021 Salty Dawg Rally to the Caribbean, which was sailing to Antigua.

There is safety in numbers, as they say. That is what the rally is all about. Weather updates are provided on a daily basis. The progress for each participating boat is tracked. The Customs and immigration check-in process is also streamlined. Now, due to COVID-19 the check-in process includes a visit from the port doctor. This rally also coordinates activities and social events at both ends; the point of origin and the destination. In this case, the point of origin was Hampton, Virginia. The destination was Antigua.

78 boats departed Hampton, most of which departed within a 6 hour period. It may seem like a lot of boats. However, in the first few days we rarely saw more than one or two other boats. After that, we could not see any except in a very rare instance. We knew some were close (within 25-30 miles) because we heard them on the VHF radio.

I was sailing on a Freedom 45 named Wayward Wind. There were three other crew members with me: Peter, the owner; Beth, Peter’s wife; Bill, a friend of Peter’s and husband to a childhood friend of mine.

Departing the Chesapeake Bay

As a crow flies, it is 1500 nautical miles (nm) from Hampton to Antigua. For this boat, in typical weather , this passage should take roughly 12 days. We did not have typical weather.

Whenever sailing east from the U.S. the Gulf Stream is always the first obstacle to overcome. The Gulf Stream is a strong current running north along the U.S. east coast. The plan was to cross the current as quickly as possible. So, departing later in the afternoon of October 30, 2021 we would reach the Gulf Stream the following morning. Then, we would start crossing the Gulf Stream in daylight hours..

It was sunset when we reached Cape Henry; the southern corner of the Chesapeake Bay where it meets the Atlantic Ocean. From land, it is just north of Virginia Beach and east of Norfolk, Virginia. We had a nice breeze from the east-southeast. The water wasn’t very choppy because the tide had turned against us and was coming into the bay.

After passing Cape Henry, we turned south and sailed along the coast towards Cape Hatteras. The waves were larger now, but still only 3-4 feet high. The sun had set. There was a new moon. So, we did not have the benefit of moonlight. The stars were shining bright, but did not provide any useable light. As the sky grew darker, so did the sea. To the north and west, there was an orange glow over the horizon; light pollution from the cities. To the south and east… just darkness. It was hard to discern the horizon from the sea.

There was a damp chill in the air, which I hate. It goes right to my bones. I was prepared for this. I had brought some base layer, a couple warm sweaters (one with a windproof liner), neoprene gloves, a wool hat and scarf. You would think I was going skiing, not sailing to the Carribean! With all that on, I was still getting chilled by the end of my 3-hour night watch. It was the moisture in the air. It gave me something to think about for my trip to Scotland.

We sailed through the night going south along the coast, about 4 miles offshore. We could see the lights on shore as we passed Virginia Beach, Corolla, NC, and other towns in the outer banks that we could not identify in the dark. Corolla is easily identified by the Currituck Lighthouse. We also identified the Bodie Island Lighthouse near dawn.

Crossing the Gulf Stream

The next morning, south of Bodie Island and north of Cape Hatteras, we had reached the waypoint given to us by the weather forecaster. This waypoint should be adjacent to the narrowest part of the Gulf Stream; minimizing the time and distance to cross this strong current. From here, we turned east and started crossing the Gulf Stream. It would take the better part of the next two days to break free of current.

Out on the ocean out of sight of land, no cell phones, no internet, we could still identify when we were entering the Gulf Stream waters. The water color had changed to a deep blue from the dark grey seen along the coast. The water temperature was noticeably warmer.

The winds were lighter than forecasted. Our hopes for smooth seas were smashed by the 4-5 foot chop. We had to motorsail to maintain our good speed in the waves. Motorsailing is using the sails, but also using the engine to help propel the boat.

It took two days to get clearly across the Gulf Stream. Those two days were a choppy mess. I was not feeling comfortable, but I convinced myself I would be fine. After all, I had only been sea sick once in my life…. the last time I was at sea.

I brought ginger candies, which helped a lot. Two solid days of the boat pitching and rolling was too much, though. I was once again overcome. Thankfully, Beth had Stugeron. A seasickness medication that is not sold in the U.S. It did the trick! No side effects either.

Once across the Gulf Stream everything changed. The water was a more brilliant deep blue. The air was warmer; especially at night. We were now in the tropical waters of the central Atlantic Ocean. There was no need to wear a base layer during the night watch. I didn’t need the wool scarf, or even a sweater at night. Although, I still wore the wool hat at night until we were further east; away from the cooler air coming off North America.

The winds were lighter than forecasted, but at 14 knots, Wayward Wind could sail nicely.

Squalls All Night Long

On the morning of Wednesday November 3rd, our fourth morning of this journey, the weather forecast we received warned of isolated squalls in the area for the next few days until we were farther east. After being on edge all night waiting for squalls, we had none. We had clear, starry sky all night with no signs of a squall. I sent a message to my good friends Steve and Theresa who were participating in this rally on their boat, Miss T, which was about 15 miles away and a little north of us. They had encountered three squalls that night. Other boats reported squalls on the radio as well.

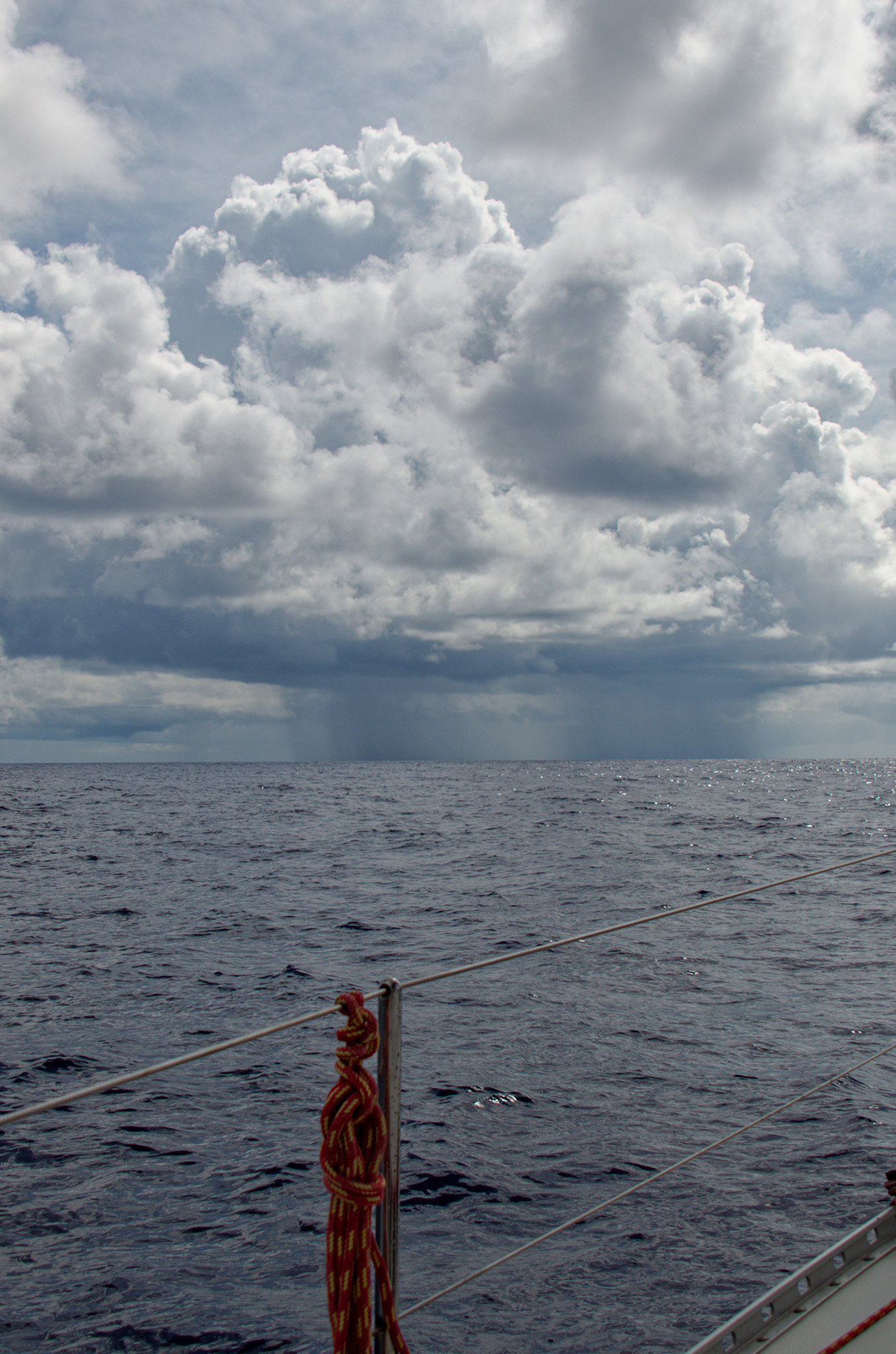

We sailed all day in light winds, making good progress. It was a clear sunny day with a long row of cumulous clouds on the horizon. Overhead, there was only blue sky. The water was a consistent deep blue. The boat pitched up and down as it sailed over the 4-5 foot waves. It may sound like large waves, but 4-5 footers are the small waves on the ocean.

When night came again, it was absent of moonlight. Just like the night before, the sky was clear and full of stars. I had forgotten how many stars can be seen with the naked eye when there is no light pollution. While on my night watch, I though, this is the same view the old explorers had.

We were alert to potential squalls, especially after hearing reports from the other boats earlier in the day. However, we made it through the night without seeing a single encounter. When the sky lightened in the morning, we knew we were just lucky. We could see several squalls ahead of us dissipating as the sun warmed the air.

That would be the last “squall-free” night.

We did not run into any storms, which cover a large geographical area. A squall is a small localized weather event. Most are just a mile or two wide. The sky was clear most of the time, day or night. There were long rows of cumulus clouds extending from the far left to the far right. During the day, the sun warmed the water and air causing the moisture to rise. At night, the clouds would release moisture it could no longer hold. It rained. It rained a cold rain from way up high in the atmosphere. This causes a sudden wind change… a squall. It will last for 10-20 minutes, then go away.

The nights were still very dark, lacking the moonlight. There was a sliver of a moon now. However, the moonrise was at 0830 and it set around 1900 (7 pm). Looking straight overhead, I could see stars. I could see stars all around. The Big Dipper and Cassiopeia are used to find the north star, but I couldn’t find them. Being so far south, I knew they would be closer to the horizon. There were no stars close to the horizon.

On night watch during that first week, the horizon was faintly visible most of the time. When the blackness of the sky blended with the water and there was no discernible horizon, I knew there was a line of clouds ahead, and possibly squalls.

So the stars were the key to seeing a cloud and potential squall at night. Wayward Wind had radar. A modern radar that can show the rain. However, the boat is moving at a relatively slow rate and the clouds are moving just a little faster. It’s not enough to find a squall, even if you can see it. It’s about 8 miles away when you identify it. So, depending on speed and direction the squall would be upon us between 10-40 minutes. In the dark, it could be sooner.

The key is to know the direction of the True Wind. The weather and squalls follow the True Wind. Knowing that, you know what direction the squall is moving and can estimate whether it will pass in front of the boat, behind the boat, or go right over head. When it goes overhead, the 10-14 knot winds will climb to near 30 knot winds over a period of about 20 seconds.

Thankfully, Peter has sailed south several times and was a wealth of knowledge and an excellent teacher for how to handle a sudden squall. Typically, I sail much farther north and have dealt with many storms, but only one squall, which we managed to avoid at that time. I learned a lot about how to deal with squalls from Peter. There were plenty of learning opportunities during this voyage. We were hit by 3 or more squalls for 10 nights.

In the morning, squalls go away, gradually. The sun warms the air. Warm air can hold more moisture. The almost overcast morning sky would gradually clear up shortly after the squalls dissappeared.

Then, the warmer air starts to rise, carrying more moisture back to higher altitudes and the whole whole process starts all over again.

Sunrise and Sunset

This sailing adventure was not all about squalls as it may seem at this point. After crossing the Gulf Stream, squalls were the major obstacle we encountered.

As mentioned previously, the sky was fairly clear. We had no storms. If I recall, there was just one overcast day. We were greeted each morning with a beautiful sunrise to start our day.

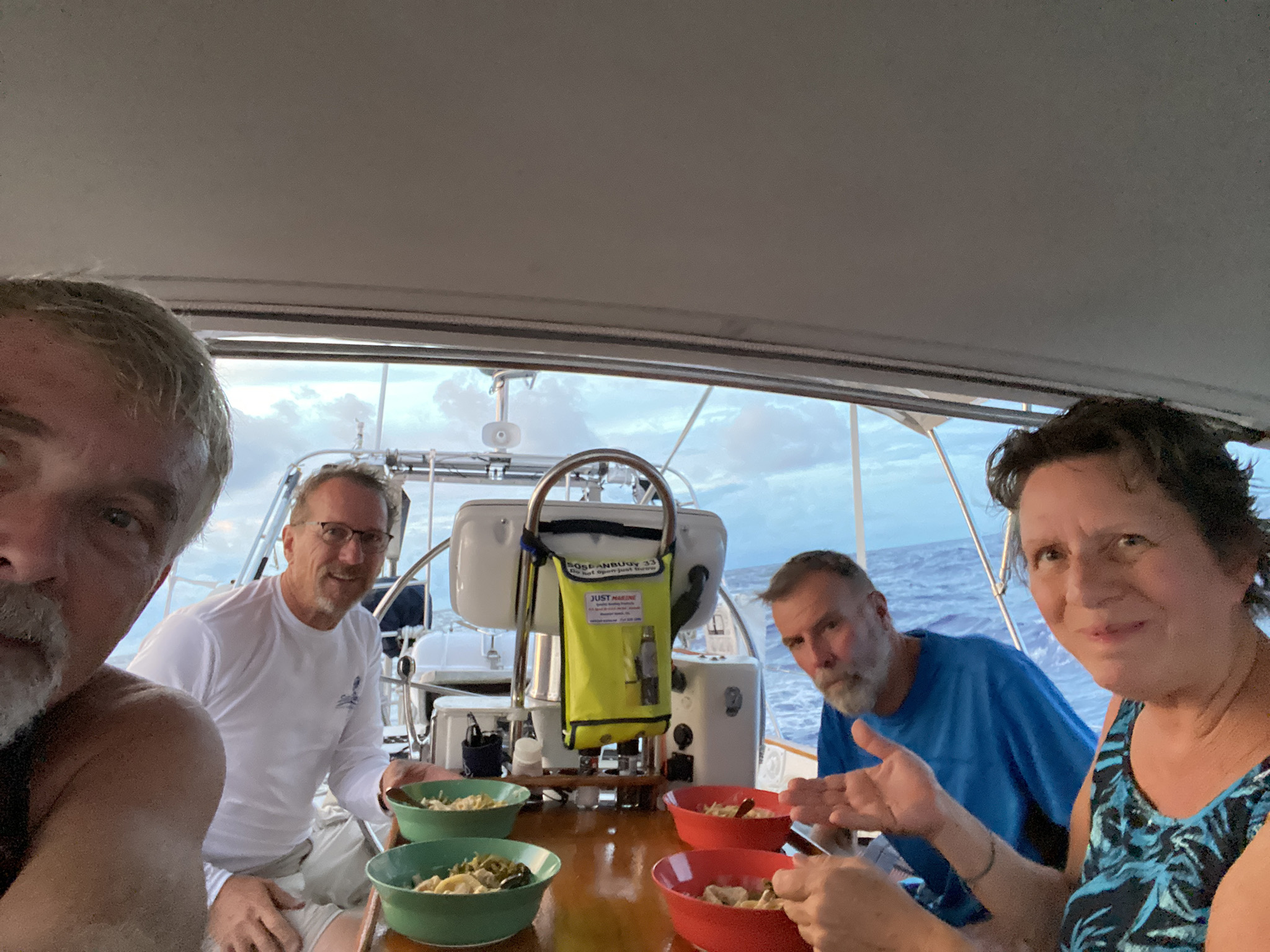

The days were sunny. In the evening, we would all sit at the cockpit table for a dinner that Beth had prepared for us. Breakfast was usually an individual’s responsibility. Beth made many of our breakfast meals and most of the lunches as well. Although we didn’t always sit together for these meals.

After dinner, we were blessed with sunsets that could only be rivaled by the next day’s sunrise. All sunrise and sunsets were beautiful. However, there were just a few that were absolutely spectacular!

There were a few things missing, which surprised me. I didn’t see any dolphins! In the past, sailing further north, I would see dolphins almost every day! There were no whales, jelly fish, or sea turtles either.

A Few Things Broke Along the Way.

When the wind picked up, so did the waves. Sometimes, the waves picked up first; giving us a warning that stronger winds were on their way. The weather router said we should continue east until about 63 degrees west longitude. That’s east of Bermuda by several hundred miles. In an attempt to do this, the boat pounded into the waves. At night, the waves couldn’t be seen. With higher winds from squalls, the boat pounded more. A few things broke along the way. The owner was well prepared and had spare parts for most issues.

Freedom boats have free-standing masts. There is no standing rigging to hold the mast up and in-place. However, there is a forestay. This is used to hold the jib. One dark night the boat was pounding as the bow plummeted off the waves and crashed back down into the water. I was asleep in my berth when I was woken up suddenly by an unusual crashing sound. I lay there listening intently. Peter and Bill were standing the night watch. So, there was no need for me to go up on deck unless called to do so.

I fell back to sleep. The pounding had seemed to stop… all the pounding. We were sailing smoothly. What I found out in the morning, was the forestay had parted from the mast and came crashing down. Bill and Peter gathered the jib and tied it off; waiting for morning light. Without the jib, Wayward Wind had slowed down. So, it was no longer going fast enough to crash off the waves.

We separated the jib from the forestay, tied the sail and its boom to the port side stanchions, and ran the forestay back along the starboard deck. Peter determined it was a small fitting that had broken, but couldn’t be fixed until we reached Antigua.

Sailing without a jib meant we were unable to point. That means we needed to sail in a direction that allowed the wind to come from the side of the boat, or behind. We were still able to continue east. Without a jib, turning south could be a problem.

Peter had a spare jib on the boat. A conventional jib. We knew we had to jury-rig conventional lines on a boat that was far from conventional. The seas were too rough to make the rig change right away. It took two days for the seas to calm enough for a person to work on the bow of the boat safely.

During this time, the catamaran, Side Two, came sailing by. It was nice that they came by fairly close, rather than 4 miles away on the horizon. I grabbed my camera and took a few photos of them.

Without a jib, Side Two gradually slipped over the horizon. Little did we know at that time, but this was not the last we would see of Side Two.

When it was safe, we used a spare halyard as a forestay and attached the spare jib to that. Peter had blocks that allowed us to run sheets (lines used to trim the sail) back to the cockpit. There was no traditional sheet winch at the side of the cockpit because the standard jib was self tacking. Further, there were only two winches; both on the cabintop. We managed to get this setup working and the boat sailed great!

We spent many days making changes and repairs to the Wayward Wind. Nothing was so serious as to jeopardize our journey.

Another problem we had was the AIS worked intermittently. AIS is the Automated Identification System. This is where Wayward Wind broadcast the boat name, position, speed, etc. so that other boats and ships are alerted to our presence. We found the antenna, at the top of the mast, was stuck and being grounded. This was something else to be repaired once we reached Antigua.

Approaching Antigua

We were finally heading south towards Antigua. Our destination was about two days away if the forecasted easterly trade winds appear, which they never did. With the lighter winds from the northeast, it took three days to reach Antigua.

I was standing the late night watch. This allowed me to watch the sky gradually brighten as the sun approached in the morning. It also meant I was on watch during the peak of the squall period.

While on watch, I noticed the lights of a ship approaching us. I hailed them on the VHF radio to confirm they could see us. They confirmed they did not have our AIS, but did have us on radar. This was a Dutch container ship, they were headed for Rotterdam. It was still very dark out. I decided to grabbed my camera and took several shots as the ship passed by. It was only the second ship that came within a visual range. Most photos were unexpectedly blurry. Somehow, this one came out fairly well.

It was a beautiful morning. We had to dodge a few squalls on the east end of the island. As we were about to turn west and head for Falmouth Harbour, a familiar voice came over the radio. It was Side Two. They were behind us and about to pass for a second time. They were running low on fuel several days before and were unable to motorsail during some very calm weather.

This passage took us 14 days, which was about the average for all boats in the rally. Of those 14 days, we motorsailed nine days, at least for part of the day. Wayward Wind carried more than enough fuel. However, many boats had to conserve their fuel and sail slowly in the light wind conditions.

The next, and final section of this Antigua trip, I will be writing about Antigua itself and some of the activities we participated in.

This is fascinating! I love learning about the weather and relationship between the squalls and air temperature and that warm air holds moisture then releases it-that whole cycle. The gulf stream experience with bundling up then warming up…it made it real . Visceral. Many nautical terms are new to me-I had to google ‘jib’.

“A saying that has taken its place in the English language as meaning, originally, that a person was recognized by the shape of his (her) nose. It has now come to indicate what someone thinks of a person’s appearance or demeanor: ‘I like the cut of his jib’, ‘I like his attitude.’ The term originated in the sailing navies of the mid-18th century, when the nationality of warships sighted at sea could be accurately determined by the shape of their jib long before the national flag could be seen. For instance, French jibs were cut much shorter on the luff than English ones, giving a distinctly more acute angle in the clew.” Now I have to look up ‘luff’.